One of the things I insist all my undergraduates learn at the beginning of each of my classes in American history is basic American geography. This sounds terribly basic, I know, but no one ever bothered to teach it to me (or at least, if they did, I wasn’t paying attention), and once I started

teaching it, I discovered that no one had ever taught it to most of my students, either.

teaching it, I discovered that no one had ever taught it to most of my students, either.I don’t do anything fancy. I start with a physical map of North America (with an inset of Hawaii, of course, pointing out the great piece of trivia that, thanks to Hawaii, America has six time zones. Then I tell them that they must know the East Coast, the West Coast, the Gulf Coast, Canada and Mexico, and three mountain ranges: the Appalachians, the Rockies, and the Sierra Nevada. I talk a bit about why each has been important in some major development (using the Donner Party for the Sierra Nevada, to keep them awake). I point out the Great Plains and the Great Basin and explain the low rainfall and high winds that create such distinctive features there, showing some of the scenery from those sections.

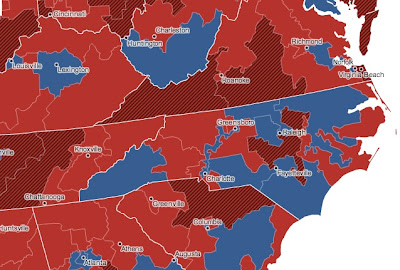

But the natural elements on which I spend the most time in my introduction to American geography are the Ohio River, the Mississippi River, and the Missouri River.

The Mississippi is the great artery of what became the United States, and figures prominently in most economic developments until after the Civil War (this is an easy one, since most of them have heard of the Mississippi, and maybe even have read Huckleberry Finn).

Then I turn to the Ohio. No one can understand early American history without understanding the Ohio River, the incredible fertility of the land around it, the determination of Indians to hold it, the line it created between slavery and freedom. (Huck can help here, too, since he and Jim went down the Mississippi River to reach freedom—counterintuitive until I explain they were trying to get down the Mississippi far enough to get up the Ohio.)

Then, balancing the importance of the Ohio on the western side of the Mississippi, there’s the Missouri River. The Missouri gets short shrift in American History texts and courses, it seems to me, and it shouldn’t. It dominates the West as thoroughly as the Ohio dominated the East in an earlier time. Just a few obvious points: It was the Missouri that offered Lewis and Clark a highway to the West Coast at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The

land around the upper Missouri has always had some of the best hunting in the country, making it highly prized both by the native people who managed the lands before the coming of easterners, and by the interlopers who started arriving in the 1860s. It was this region, of course, that produced Red Cloud and Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and it was to wrest control of this land that General George A. Custer marched his men to the banks of the Greasy Grass in 1876. Only a few decades later, it was the Missouri River that seemed to offer the answer when the dry plains defeated hopeful western farmers. Fifteen dams now slow the river, creating reservoirs and taming floods to make the upper Northwest more productive and habitable.

land around the upper Missouri has always had some of the best hunting in the country, making it highly prized both by the native people who managed the lands before the coming of easterners, and by the interlopers who started arriving in the 1860s. It was this region, of course, that produced Red Cloud and Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and it was to wrest control of this land that General George A. Custer marched his men to the banks of the Greasy Grass in 1876. Only a few decades later, it was the Missouri River that seemed to offer the answer when the dry plains defeated hopeful western farmers. Fifteen dams now slow the river, creating reservoirs and taming floods to make the upper Northwest more productive and habitable.And that, of course, is the reason for this post. How many of our students—at least those east of the Mississippi—paid any attention to the historic and terrifying flooding of the Missouri River this spring? A large melting snowpack has combined with torrential rains to create a flooding emergency that rivals Hurricane Katrina. Levies are breaking up and down the river, sending evacuees fleeing as the water covers homes and fields, as well as the Fort Calhoun Nuclear Station in Nebraska (which does not appear to be in danger). Reuters is reporting that the floods along the Missouri and the Mississippi have damaged about 2.5 million acres of farmland in the U.S. which seems likely to hurt farm production. It’s probable that this will, in turn, drive up food prices. This is not an unimportant weather event.

Already, observers are speculating about what this disaster says about the way America has historically approached the taming of the Missouri. The management of water in the West has long been a subject that interests western historians, but seemed to have drifted by most people in the East. And now that debate has sprung pretty dramatically out of the pages of historical journals and into the headlines. This year’s disastrous flooding suggests that American historians might be able to do the country a service by making sure all their students know what the Missouri River is, why it’s been important in the past, and just how vital its management has been, and is still, to the nation today.