Steven Cromack

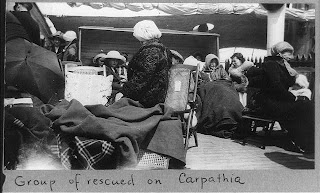

April 15, 2012 marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic. In honor of the centennial, events are taking place across the world—in Belfast, in Southampton, in

New York, and even in Branson, Missouri. James Cameron re-released his 1997 blockbuster in IMAX 3-D, and there are a slew of new books appearing on the shelves. What is it about the Titanic that makes it so captivating? The answer, I believe, is that the many stories, all of which compose the master story, have a universal and generational appeal. They resonate with the deepest elements of who we are as human beings, or the “collective unconscious” articulated by Carl Jung, beneath the surface of our iceberg-like minds.

In terms of maritime history, the Titanic does not hold any special records—it was neither the largest ship to sink, nor did it claim the most lives. Yet, no other maritime disaster in history has captivated the public’s attention more so than the Titanic’s sinking. The academy as a whole does not consider the ship significant in the grand scheme of examining change over time. Indeed, of the many books on the subject published very few come from academic presses. Historians consider the Titanic story merely as “popular history,” or a history in which the “past is mobilized for a wide variety of purposes including . . . profit-making entertainment.”[1]

The tale of the Titanic, however, is more than “popular history” or “profit-making entertainment.” The Titanic endures in the same way that Shakespeare’s works, or even those of Sophocles or Euripides, endure. It lives on, even a century later, because the narrative contains stories of heroes and villains, “what if” scenarios, secrets, mysteries, stories of romance, and of heart-wrenching loss. It warns of the dangers of hubris and is an example of Edward Lorenz’s “Chaos Theory” and “Murphy’s Law.” It is a Petri dish in which historians, sociologists, anthropologists, and psychologists can examine and argue over the deepest elements of human nature: what happens when human beings find themselves in a dire scenario.

The story of Titanic is an intricate masterpiece of characters, narratives, and sub plots upon sub plots. There is story that everyone can admire or anguish over. Perhaps it is the character

of the “Unsinkable” Molly Brown, who took an oar herself, something undoubtedly Susan B. Anthony would have done, and insisted that her virtually empty lifeboat go back and pull survivors out of the water. Such an act would have put her and others at risk of being capsized. Or, maybe, it is the awesome love which Ida Strauss showed her husband, Isidor Strauss, the co-owner of Macy’s Department Store, when she refused to leave her husband to die on the ship. Another person, at some point during the night, went down below and released the passengers’ dogs from the kennel.

All of these mini stories weave together to form the “big picture,” or the master story. Robert Ballard, the discoverer of the wreck, said that the disaster was “truly a tragedy worthy of Shakespeare himself” because:

Mankind, in all its hubris, designs an unsinkable ship that goes down on its maiden voyage. Where the captain evokes the British ideal and instructs the crew to stand at their station and die while the band plays on even as the owner sneaks into one of the few lifeboats and gets away. Where women and children go first, unless you are third class, and where a rescue ship [the Californian] stands by and does nothing.[2]

The Titanic is also Greek tragedy, in line with those works of Euripides or Sophocles. It recalls a tragic hero, caught between the always-dueling forces of the nomoi and physis (pronounced foo-sys). The nomoi are the human traditions, conventions, and laws created and enforced by humans. Physis is “nature”—those forces and laws that do not originate in human will and are outside of human control (fate, chance, or fortune). The ship was a human creation of greed, avarice, and humankind’s attempt to dominate the ocean. At the same time, so many factors outside the control of those on board conspired, much like the Greek Gods, to seal the vessel’s fate. The sea was dead calm that night, making it nearly impossible to see the base of the iceberg. The binoculars went missing, the steel was not designed for the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, and according to one

new astronomy theory, the moon’s position that year affected the ice pattern.

Such a tragedy “worthy of Shakespeare,” or of the Greeks, resonates with the deepest elements of the human psyche. Our minds, ironically, are like icebergs, in that we only use a small portion of our

brains. Beneath the surface, beneath the layers of baseball trivia, historical timelines, and mathematical theorems is the “unconscious.” There, anything goes. It is where our feelings, the ones we cannot control, and the ones that shape society—love, passion, desire, etc—reside. In 1934, Carl Jung articulated the idea of a “collective unconscious,” or the thought that thousands of years of human history exists inside of every person. We, as humans, choose to make things sacred (and unsacred), shape and mold society according to these passions and feelings that rise from the unconscious to the surface.[3] Jung wrote in his

Psychology of the Unconscious, “This world is empty to him alone who does not understand how to direct his libido toward objects, and to render them alive and beautiful for himself, for Beauty does not indeed lie in things, but in the feeling that we give them.”[4]

The stories of love and loss, mystery and fate, all interwoven together in the Titanic live on in 2012 because they appeal to our deepest emotions. The Titanic story will undoubtedly live on for another century. In many ways, the ship itself was just the “tip of the iceberg.”

______________

1. Peter Sexias, Theorizing Historical Consciousness (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 10.

2. Interview with Robert Ballard, University of Rhode Island Department of History, Online at: http://www.uri.edu/news/ballard/quest.htm#2

3. Victor Daniels, Handout on Carl Gustav Jung. Sonoma State University. Online at: http://www.sonoma.edu/users/d/daniels/Jungsum.html

4. C.G. Jung, Psychology of the Unconscious (Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc., 2002), 193.