The recent effort to legalize and regulate the sale of marijuana has brought to light a number of new studies of Prohibition. They have some fascinating information in them—like the fact that booze runners started the car racing industry (a theme later picked up in The Dukes of Hazzard).

Who knew?

Another thing many of the blogs mention is equally surprising. During Prohibition, entrepreneurs outfitted ships as nightclubs and towed them three miles offshore into international waters where they could legally serve liquor. In the early morning, they towed the floating bars back to port.

While this is interesting from many perspectives, it is of interest to economic historians and those involved in maritime history because it reflected the destruction of the New England sailing fleet at the beginning of the twentieth century. Those huge wooden schooners had owned the oceans for the decades spanning the turn of the century, carrying grain to Asia, guano to Europe, and manufactured goods everywhere. By 1900, though, they had been overtaken by metal steamers and spent their last days limping to their final resting places.

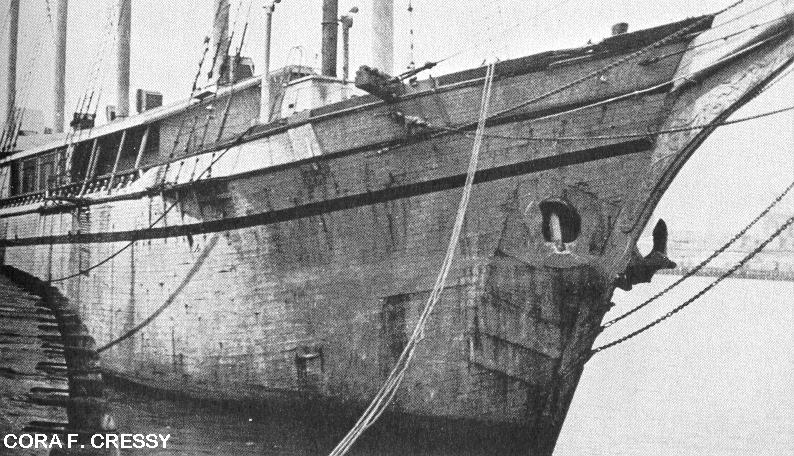

One of these schooners was the Cora F. Cressy, and her story illustrates this dramatic economic change.

The Cora Cressy was built in 1902 at the Percy & Small shipyard in Bath, Maine (now home to the wonderful Maine Maritime Museum, which has an exhibit of some of the Cora Cressy’s fittings). She was a five-masted schooner, 273 feet long and 2499 tons: a fast sailor that could carry 4000 tons of coal. She was like other schooners at the time, cheaper to replace than to repair. Owners deferred maintenance and ran her until she took great damage in a 1928 storm.

In 1929, the Cora Cressy’s owners sold her to become a Prohibition nightclub off the coast of New England, a role she held into the 1930s.

The end of Prohibition left the Cory Cressy without a career. The owner of a lobster pound in Medomak, Maine, bought her as a storage tank for lobsters, but found the old Percy & Small workers had built her too well—it was impossible to drill enough holes in her hull to enable water to circulate. She became a hulk of a breakwater, half buried in the mud, barnacles, and mussels that grew up around her. Well into the 1980s, you could peek through the Cora Cressy’s broken timbers to see the tattered maroon curtains from her nightclub days.

And there her remains sit today, a testimony to the fall of New England’s sailing fleet from economic powerhouse, to Prohibition speakeasy, to wreckage.

8 comments:

The tradition of skirting prohibitive laws continues today. On any given night one can board a boat from Miami to international waters. Once the boat is three miles out people gamble. Then the boat returns to shore in the morning.

Wow! I had no idea.

Is that a gangster movie waiting to happen or what?! (Or maybe a Carl Hiaasen book, come to think of it.)

You can gamble on the ferry out of Portland, to Nova Scotia...can't you? Used to be able to.

I was on that as an eight-year-old!

Is THAT why there was gambling on it? I thought it was because we were in Canadian waters!

True, but also -- water is somehow magical. There's riverboat gambling on the Mississippi, the Ohio, and Lake Michigan. In 1996, the Coast Guard Reauthorization Act exempted Lake Michigan from the Johnson Act, to allow Indiana to operate casino boats.

The real question -- can you sail out to the middle of Lake Tahoe and light a joint?

Or, can you build a small pond in your back yard, put a floating platform on it and make it an "anything-goes party zone."

The water thing really is hilarious and arbitrary. I remember one of the casinos in Kansas City, MO, was built over water, even though it never moved from that spot. AND, they had "boarding times" for folks to be admitted onto the gambling floor.

Maybe the idea here is that the hassle just makes it more difficult.

I've always thought that the peculiar laws of the sea were what made water rules so different than land (including burials and weddings, for example), but these last two comments bring back my long-ago training in Folklore and Mythology.

Water can be seen as a liminal space. Humans traditionally have seen water as a powerful element: Magic doesn't work in or over water; water purifies; it can save you or kill you, depending on whether you're dehydrated or drowning.

I wonder how much of that magic thinking still operates at some level when people deal with water?

Or is it that sailors and watermen are traditionally scofflaws and pirates, who will always use any loophole they can to avoid regulation?

Or maybe the two things feed each other? (Is it obvious that I've been reading rather dry legislation all morning?!)

With the change of seasons, I'm reminded of when the water isn't quite as liminal. Every winter in Minnesota, little temporary communities of fishing houses appear on the ice. On bigger lakes, these villages can be out of sight of the shore, and some of them get quite big. Nowadays, with GPS, you can put them right where they were last year, but even before that, they often looked the same, year after year.

Some of the purists think it's cooler to take a temporary shelter out on a sled, and set up away from the crowds. You miss out on the party atmosphere, but you get the quiet and the fish. And it is quiet. Just the wind, geese calling to each other on the flyway 1/2 mile overhead, and the occasional rifle-shot crack of moving ice. Makes the fish taste better.

Post a Comment