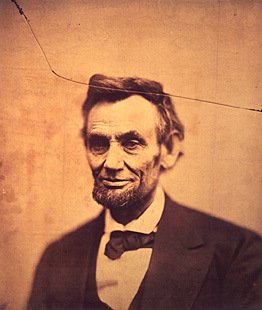

Seven score and seven years ago Abraham Lincoln brought forth on this continent a new sentiment, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Civil War historians know the Gettysburg Address so well

that writing about it seems almost trite. We lecture about it; we teach it in discussion groups; we know it by heart.

that writing about it seems almost trite. We lecture about it; we teach it in discussion groups; we know it by heart.It is hardly innovative to note that this famous speech marked a turning point in the meaning of the Civil War. With his masterful invocation of the Declaration of Independence, President Lincoln redefined the conflict. No longer would it be a fight solely to prevent the dismembering of the Union; from 1863 forward, it would be a struggle to guarantee that everyone born in America would have equal access to education, economic opportunity, and the law.

Lincoln’s declaration was truly a rededication of America. This, as much as anything, earned Lincoln a dominant place in the American pantheon. His words spoke directly to the true meaning of modern America.

But this belief in equality in America has never gone uncontested. It seems that Lincoln could have been speaking to the present when he warned at Gettysburg that the living must defend the legacy of the dead: “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

A year to the day after delivering the Gettysburg Address, on November 19, 1864, President Lincoln offered another epigram about America.

Among the blizzard of correspondence that crossed his desk that day was a brief note the President jotted to General William S. Rosecrans. In it, Lincoln stayed the execution of Confederate Major Enoch O. Wolf, convicted of murdering Major James Wilson and six members of the cavalry of the 3rd Missouri State Militia.

The President freely admitted he did not know anything of the circumstances of the case, and that the decision about Wolf’s future was in Rosecrans’s hands. He had suspended the sentence because he wanted to make sure Rosecrans understood that the general’s own inclinations were unimportant, and that he must do only what was best for the nation. “I wish you to do nothing merely for revenge,” Lincoln wrote, “but that what you may do, shall be solely done with reference to the security of the future.”

After 1863, Lincoln turned his masterful political skills solely toward securing equality for all Americans. As he counseled Rosecrans to do, he lost himself in his vision for the nation. Lincoln took hit after political hit, deflected opponents’ wrath with wry stories, and tried to find middle ground with his enemies. As he indicated to Rosecrans, he had only one goal: to make the American dream accessible to all Americans.

In the end, Lincoln was unable to blunt the hatred of the men who saw his defense of equality as an assault on civilization. By November 19, 1865, the President was dead. But he left behind him a new vision of America, and a charge to those born after the night that he, too, died for it: “that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.”

2 comments:

Isn't that something: he was four score and seven from the founders, and seven score and seven from us.

So do you think Lincoln's drive to achieve this goal of liberty and equal opportunity caused him to overlook the buildup of national power? Did he think it was a temporary wartime concentration that would correct itself? A necessary evil to secure this American legacy for everyone? Or did he lose track of the details, where the devil was?

One of my favorite bits of wit from Lincoln, which you point out he used to get through the dark days, is this response to someone who called him two-faced:

"If I were two-faced, would I be wearing this one?"

Post a Comment