In a post a few weeks ago, I asked what an American city might have looked like in 1848. An amazingly detailed daguerreotype of a booming Cincinnati gives us a good idea. It's a tremendous resource.

That got me thinking about a new series for the blog. The idea is to post a portion of a primary source from that offers an insightful, evocative portrait of a place, a time, a people. Some questions that sources might answer: What was it like to live in Paris as the Black Death decimated the city? What might it have been like to walk down Cheapside in Dickensian London? How did it feel to live in Pompeii on the eve of the city's destruction? What was it like to be a 16th-century Jesuit missionary in Japan? (Please pass along your favorite primary sources.)

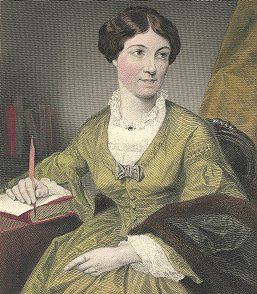

For the first installment I've chosen Harriet Martineau's (1802-1876) interesting portrait of Washington, DC, (1835) populated as it was by oddballs from the sticks, society ladies, gabbing

politicians, and some giants of the day. (A came across this in Allan Nevins, ed., American Through British Eyes [Oxford University Press, 1948].) Martineau was an English journalist, novelist, and essayist from Norwich. Her family's falling fortunes in her youth are worthy of a Jane Austen novel. Luckily, she made a tidy living off her writing.

politicians, and some giants of the day. (A came across this in Allan Nevins, ed., American Through British Eyes [Oxford University Press, 1948].) Martineau was an English journalist, novelist, and essayist from Norwich. Her family's falling fortunes in her youth are worthy of a Jane Austen novel. Luckily, she made a tidy living off her writing.Martineau circulated among the leading movers and shakers of her era. She developed keen observational abilities and could make even complex subjects accessible to a wide audience. She wrote about the development of religions and penned essays on new economic theories. Her abolitionism and unorthodox take on religion stirred controversy in the United States and made her an infamous character for many. (See her comments below about Northerners and Southerners.)

Martineau's American travel writings--though not as well know as those by De Tocqueville, Dickens, and the Trollopes--shed light on customs, sectional differences, and the boisterous Waking Giant of America in the Age of Jackson. (Her unflinching portrait of cast-iron Calhoun, as someone who has come unhinged, or unbolted, is, pardon the pun, riveting.)

Harriet Martineau, Retrospect of Western Travel, Volume 1 (London, 1838).

In Philadelphia, I had found perpetual difficulty in remembering that I was in a foreign country. The pronunciation of a few words by our host and hostess, the dinner table, and the inquiries of visiters were almost all that occurred to remind me that I was not in a brother's house. At Washington, it was very different. The city itself is unlike any other that ever was seen,—straggling out hither and thither,—with a small house or two, a quarter of a mile from any other; so that in making calls "in the city," we had to cross ditches and stiles, and walk alternately on grass and pave menu, and strike across a field to reach a street.—Then the weather was so strange;  sometimes so cold that the only way I could get any comfort was by stretching on the sofa drawn before the fire, up to the very fender; (on which days, every person who went in and out of the house was sure to leave the front door wide open:) then the next morning, perhaps, if we went out muffled in furs, we had to turn back, and exchange our wraps for a light shawl. Then, we were waited upon by a slave, appointed for the exclusive service of our party during our stay. Then, there were canvas-back ducks, and all manner of other ducks on the table, in greater profusion than any single article of food, except turkeys, that I ever saw. Then, there was the society, singularly compounded from the largest variety of elements— foreign ambassadors, the American government, members of Congress, from Clay and Webster down to Davy Crockett, Benton from Missouri, and Cuthbert, with the freshest Irish brogue, from Georgia; flippant young belles, "pious" wives, dutifully attending their husbands, and groaning over the frivolities of the place; grave judges, saucy travellers, pert newspaper reporters, melancholy Indian chiefs, and timid New England ladies, trembling on the verge of the vortex,—all this was wholly unlike any thing that is to be seen in any other city in the world; for all these are mixed up together in daily intercourse, like the higher circle of a little village, and there is nothing else. You have this or nothing; you pass your days among these people, or you spend them alone. It is in Washington that varieties of manners are conspicuous. There the Southerners appear to the most advantage, and the New Englanders to the least: the ease and frank courtesy of the gentry of the south, (with an occasional touch of arrogance, however,) contrasting favourably with the cautious, somewhat gauche, and too deferential air of the members from the north. One fancies one can tell a New England member in the open air by his deprecatory walk. He seems to bear in mind perpetually that he cannot fight a duel, while other people can. The odd mortals that wander in from the western border cannot be described as a class ; for no one is like anybody else. One has a neck like a crane, making an interval of inches between stock and chin. Another wears no cravat, apparently because there is no room for one. A third has his lank black hair parted accurately down the middle, and disposed in bands in front, so that he is taken for a woman when only the head is seen in a crowd. A fourth puts an arm round the neck of a neighbour on either side as he stands, seeming afraid of his tall wire-hung frame dropping to pieces if he tries to stand alone: a fifth makes something between a bow and a curtsey to every body who comes near, and proses with a knowing air:—all having shrewd faces, and being probably very fit for the business they come upon. . . . (237-239)

sometimes so cold that the only way I could get any comfort was by stretching on the sofa drawn before the fire, up to the very fender; (on which days, every person who went in and out of the house was sure to leave the front door wide open:) then the next morning, perhaps, if we went out muffled in furs, we had to turn back, and exchange our wraps for a light shawl. Then, we were waited upon by a slave, appointed for the exclusive service of our party during our stay. Then, there were canvas-back ducks, and all manner of other ducks on the table, in greater profusion than any single article of food, except turkeys, that I ever saw. Then, there was the society, singularly compounded from the largest variety of elements— foreign ambassadors, the American government, members of Congress, from Clay and Webster down to Davy Crockett, Benton from Missouri, and Cuthbert, with the freshest Irish brogue, from Georgia; flippant young belles, "pious" wives, dutifully attending their husbands, and groaning over the frivolities of the place; grave judges, saucy travellers, pert newspaper reporters, melancholy Indian chiefs, and timid New England ladies, trembling on the verge of the vortex,—all this was wholly unlike any thing that is to be seen in any other city in the world; for all these are mixed up together in daily intercourse, like the higher circle of a little village, and there is nothing else. You have this or nothing; you pass your days among these people, or you spend them alone. It is in Washington that varieties of manners are conspicuous. There the Southerners appear to the most advantage, and the New Englanders to the least: the ease and frank courtesy of the gentry of the south, (with an occasional touch of arrogance, however,) contrasting favourably with the cautious, somewhat gauche, and too deferential air of the members from the north. One fancies one can tell a New England member in the open air by his deprecatory walk. He seems to bear in mind perpetually that he cannot fight a duel, while other people can. The odd mortals that wander in from the western border cannot be described as a class ; for no one is like anybody else. One has a neck like a crane, making an interval of inches between stock and chin. Another wears no cravat, apparently because there is no room for one. A third has his lank black hair parted accurately down the middle, and disposed in bands in front, so that he is taken for a woman when only the head is seen in a crowd. A fourth puts an arm round the neck of a neighbour on either side as he stands, seeming afraid of his tall wire-hung frame dropping to pieces if he tries to stand alone: a fifth makes something between a bow and a curtsey to every body who comes near, and proses with a knowing air:—all having shrewd faces, and being probably very fit for the business they come upon. . . . (237-239)

Our pleasantest evenings were some spent at home in a society of the highest order. Ladies, literary, fashionable, or domestic, would spend an hour with us on their way from a dinner, or to a ball. Members of Congress would repose themselves by our fire side. Mr. Clay, sitting upright on the sofa, with his snuff-box ever in his hand, would discourse for many an hour, in his even, soft, deliberate tone, on any one of the great subjects of American policy which we might happen to start, always amazing us with the moderation of estimate and speech which so impetuous a nature has been able to attain. Mr. Webster, leaning back at his ease, telling stories, cracking jokes, shaking the sofa with burst after burst of laughter, or smoothly discoursing to the perfect felicity of the logical part of one's constitution, would illuminate an evening now and then. Mr. Calhoun, the cast-iron man, who looks as if he had never been born, and never could be extinguished, would come in sometimes to keep our understandings upon a painful stretch for a short while, and leave us to take to pieces his close, rapid, theoretical, illustrated talk, and see what we could make of it. We found it usually more worth retaining as a curiosity than as either very just or useful. His speech abounds in figures, truly illustrative, if that which they illustrate were but true also. But his theories of government, (almost the only subject on which his thoughts are employed,) the squarest and compactest theories that ever were made, are composed out of limited elements, and are not therefore likely to stand service very well. It is at first extremely interesting to hear Mr. Calhoun talk; and there is a never-failing evidence of power in all he says and does, which commands intellectual reverence: but the admiration is too soon turned into regret,—into absolute melancholy. It is impossible to resist the conviction that all this force can be at best but useless, and is but too likely to be very mischievous. His mind has long lost all power of communicating with any other. I know no man who lives in such utter intellectual solitude. He meets men and harangues them, by the fire-side, as in the Senate: he is wrought, like a piece of machinery, set a-going vehemently by a weight, and stops while you answer: he either passes by what you say, or twists it into a suitability with what is in his head, and begins to lecture again. Of course, a mind like this can have little influence in the Senate, except by virtue, perpetually wearing out, of what it did in its less eccentric days: but its influence at home is to be dreaded. There is no hope that an intellect so cast in narrow theories will accommodate itself to varying circumstances: and there is every danger that it will break up all that it can, in order to remould the materials in its own way. (242-244)

which so impetuous a nature has been able to attain. Mr. Webster, leaning back at his ease, telling stories, cracking jokes, shaking the sofa with burst after burst of laughter, or smoothly discoursing to the perfect felicity of the logical part of one's constitution, would illuminate an evening now and then. Mr. Calhoun, the cast-iron man, who looks as if he had never been born, and never could be extinguished, would come in sometimes to keep our understandings upon a painful stretch for a short while, and leave us to take to pieces his close, rapid, theoretical, illustrated talk, and see what we could make of it. We found it usually more worth retaining as a curiosity than as either very just or useful. His speech abounds in figures, truly illustrative, if that which they illustrate were but true also. But his theories of government, (almost the only subject on which his thoughts are employed,) the squarest and compactest theories that ever were made, are composed out of limited elements, and are not therefore likely to stand service very well. It is at first extremely interesting to hear Mr. Calhoun talk; and there is a never-failing evidence of power in all he says and does, which commands intellectual reverence: but the admiration is too soon turned into regret,—into absolute melancholy. It is impossible to resist the conviction that all this force can be at best but useless, and is but too likely to be very mischievous. His mind has long lost all power of communicating with any other. I know no man who lives in such utter intellectual solitude. He meets men and harangues them, by the fire-side, as in the Senate: he is wrought, like a piece of machinery, set a-going vehemently by a weight, and stops while you answer: he either passes by what you say, or twists it into a suitability with what is in his head, and begins to lecture again. Of course, a mind like this can have little influence in the Senate, except by virtue, perpetually wearing out, of what it did in its less eccentric days: but its influence at home is to be dreaded. There is no hope that an intellect so cast in narrow theories will accommodate itself to varying circumstances: and there is every danger that it will break up all that it can, in order to remould the materials in its own way. (242-244)

sometimes so cold that the only way I could get any comfort was by stretching on the sofa drawn before the fire, up to the very fender; (on which days, every person who went in and out of the house was sure to leave the front door wide open:) then the next morning, perhaps, if we went out muffled in furs, we had to turn back, and exchange our wraps for a light shawl. Then, we were waited upon by a slave, appointed for the exclusive service of our party during our stay. Then, there were canvas-back ducks, and all manner of other ducks on the table, in greater profusion than any single article of food, except turkeys, that I ever saw. Then, there was the society, singularly compounded from the largest variety of elements— foreign ambassadors, the American government, members of Congress, from Clay and Webster down to Davy Crockett, Benton from Missouri, and Cuthbert, with the freshest Irish brogue, from Georgia; flippant young belles, "pious" wives, dutifully attending their husbands, and groaning over the frivolities of the place; grave judges, saucy travellers, pert newspaper reporters, melancholy Indian chiefs, and timid New England ladies, trembling on the verge of the vortex,—all this was wholly unlike any thing that is to be seen in any other city in the world; for all these are mixed up together in daily intercourse, like the higher circle of a little village, and there is nothing else. You have this or nothing; you pass your days among these people, or you spend them alone. It is in Washington that varieties of manners are conspicuous. There the Southerners appear to the most advantage, and the New Englanders to the least: the ease and frank courtesy of the gentry of the south, (with an occasional touch of arrogance, however,) contrasting favourably with the cautious, somewhat gauche, and too deferential air of the members from the north. One fancies one can tell a New England member in the open air by his deprecatory walk. He seems to bear in mind perpetually that he cannot fight a duel, while other people can. The odd mortals that wander in from the western border cannot be described as a class ; for no one is like anybody else. One has a neck like a crane, making an interval of inches between stock and chin. Another wears no cravat, apparently because there is no room for one. A third has his lank black hair parted accurately down the middle, and disposed in bands in front, so that he is taken for a woman when only the head is seen in a crowd. A fourth puts an arm round the neck of a neighbour on either side as he stands, seeming afraid of his tall wire-hung frame dropping to pieces if he tries to stand alone: a fifth makes something between a bow and a curtsey to every body who comes near, and proses with a knowing air:—all having shrewd faces, and being probably very fit for the business they come upon. . . . (237-239)

sometimes so cold that the only way I could get any comfort was by stretching on the sofa drawn before the fire, up to the very fender; (on which days, every person who went in and out of the house was sure to leave the front door wide open:) then the next morning, perhaps, if we went out muffled in furs, we had to turn back, and exchange our wraps for a light shawl. Then, we were waited upon by a slave, appointed for the exclusive service of our party during our stay. Then, there were canvas-back ducks, and all manner of other ducks on the table, in greater profusion than any single article of food, except turkeys, that I ever saw. Then, there was the society, singularly compounded from the largest variety of elements— foreign ambassadors, the American government, members of Congress, from Clay and Webster down to Davy Crockett, Benton from Missouri, and Cuthbert, with the freshest Irish brogue, from Georgia; flippant young belles, "pious" wives, dutifully attending their husbands, and groaning over the frivolities of the place; grave judges, saucy travellers, pert newspaper reporters, melancholy Indian chiefs, and timid New England ladies, trembling on the verge of the vortex,—all this was wholly unlike any thing that is to be seen in any other city in the world; for all these are mixed up together in daily intercourse, like the higher circle of a little village, and there is nothing else. You have this or nothing; you pass your days among these people, or you spend them alone. It is in Washington that varieties of manners are conspicuous. There the Southerners appear to the most advantage, and the New Englanders to the least: the ease and frank courtesy of the gentry of the south, (with an occasional touch of arrogance, however,) contrasting favourably with the cautious, somewhat gauche, and too deferential air of the members from the north. One fancies one can tell a New England member in the open air by his deprecatory walk. He seems to bear in mind perpetually that he cannot fight a duel, while other people can. The odd mortals that wander in from the western border cannot be described as a class ; for no one is like anybody else. One has a neck like a crane, making an interval of inches between stock and chin. Another wears no cravat, apparently because there is no room for one. A third has his lank black hair parted accurately down the middle, and disposed in bands in front, so that he is taken for a woman when only the head is seen in a crowd. A fourth puts an arm round the neck of a neighbour on either side as he stands, seeming afraid of his tall wire-hung frame dropping to pieces if he tries to stand alone: a fifth makes something between a bow and a curtsey to every body who comes near, and proses with a knowing air:—all having shrewd faces, and being probably very fit for the business they come upon. . . . (237-239)Our pleasantest evenings were some spent at home in a society of the highest order. Ladies, literary, fashionable, or domestic, would spend an hour with us on their way from a dinner, or to a ball. Members of Congress would repose themselves by our fire side. Mr. Clay, sitting upright on the sofa, with his snuff-box ever in his hand, would discourse for many an hour, in his even, soft, deliberate tone, on any one of the great subjects of American policy which we might happen to start, always amazing us with the moderation of estimate and speech

which so impetuous a nature has been able to attain. Mr. Webster, leaning back at his ease, telling stories, cracking jokes, shaking the sofa with burst after burst of laughter, or smoothly discoursing to the perfect felicity of the logical part of one's constitution, would illuminate an evening now and then. Mr. Calhoun, the cast-iron man, who looks as if he had never been born, and never could be extinguished, would come in sometimes to keep our understandings upon a painful stretch for a short while, and leave us to take to pieces his close, rapid, theoretical, illustrated talk, and see what we could make of it. We found it usually more worth retaining as a curiosity than as either very just or useful. His speech abounds in figures, truly illustrative, if that which they illustrate were but true also. But his theories of government, (almost the only subject on which his thoughts are employed,) the squarest and compactest theories that ever were made, are composed out of limited elements, and are not therefore likely to stand service very well. It is at first extremely interesting to hear Mr. Calhoun talk; and there is a never-failing evidence of power in all he says and does, which commands intellectual reverence: but the admiration is too soon turned into regret,—into absolute melancholy. It is impossible to resist the conviction that all this force can be at best but useless, and is but too likely to be very mischievous. His mind has long lost all power of communicating with any other. I know no man who lives in such utter intellectual solitude. He meets men and harangues them, by the fire-side, as in the Senate: he is wrought, like a piece of machinery, set a-going vehemently by a weight, and stops while you answer: he either passes by what you say, or twists it into a suitability with what is in his head, and begins to lecture again. Of course, a mind like this can have little influence in the Senate, except by virtue, perpetually wearing out, of what it did in its less eccentric days: but its influence at home is to be dreaded. There is no hope that an intellect so cast in narrow theories will accommodate itself to varying circumstances: and there is every danger that it will break up all that it can, in order to remould the materials in its own way. (242-244)

which so impetuous a nature has been able to attain. Mr. Webster, leaning back at his ease, telling stories, cracking jokes, shaking the sofa with burst after burst of laughter, or smoothly discoursing to the perfect felicity of the logical part of one's constitution, would illuminate an evening now and then. Mr. Calhoun, the cast-iron man, who looks as if he had never been born, and never could be extinguished, would come in sometimes to keep our understandings upon a painful stretch for a short while, and leave us to take to pieces his close, rapid, theoretical, illustrated talk, and see what we could make of it. We found it usually more worth retaining as a curiosity than as either very just or useful. His speech abounds in figures, truly illustrative, if that which they illustrate were but true also. But his theories of government, (almost the only subject on which his thoughts are employed,) the squarest and compactest theories that ever were made, are composed out of limited elements, and are not therefore likely to stand service very well. It is at first extremely interesting to hear Mr. Calhoun talk; and there is a never-failing evidence of power in all he says and does, which commands intellectual reverence: but the admiration is too soon turned into regret,—into absolute melancholy. It is impossible to resist the conviction that all this force can be at best but useless, and is but too likely to be very mischievous. His mind has long lost all power of communicating with any other. I know no man who lives in such utter intellectual solitude. He meets men and harangues them, by the fire-side, as in the Senate: he is wrought, like a piece of machinery, set a-going vehemently by a weight, and stops while you answer: he either passes by what you say, or twists it into a suitability with what is in his head, and begins to lecture again. Of course, a mind like this can have little influence in the Senate, except by virtue, perpetually wearing out, of what it did in its less eccentric days: but its influence at home is to be dreaded. There is no hope that an intellect so cast in narrow theories will accommodate itself to varying circumstances: and there is every danger that it will break up all that it can, in order to remould the materials in its own way. (242-244)For more:

"Miss Martineau's Retrospect of American Travel," Tait's Edinburgh Magazine (April 1838).

Harriet Martineau, Maria Weston Chapman, Harriet Martineau's Autobiography, Volume 1 (London, 1877).

Harriet Martineau, The Martyr Age of the United States: An Appeal on Behalf of the Oberlin Institute in Aid of the Abolition of Slavery (Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1840).

1 comment:

If possible, please send via email the 1848 Cincinnati view you mentioned. Thank you!

Post a Comment