Randall Stephens

See the new issue of

Historically Speaking, now available on the Project Muse site. (Most will only be able to access the full issue from a university computer or with a university account.)

I excerpt here part of my review with

Larry Friedman, professor of history in Harvard’s Mind,

Brain, and Behavior Initiative at Harvard University. Friedman has published a variety of books and articles on the history of psychology, the history of race and racism, and the history of social reform movements. His books include:

The White Savage: Racial Fantasies in the Postbellum South (Prentice-Hall, 1970),

Inventors of the Promised Land (Knopf, 1975),

Gregarious Saints: Self and Community in American Abolitionism, 1830–1870 (Cambridge University Press, 1982),

Menninger: The Family and the Clinic (Knopf, 1990) and a definitive study of developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst

Erik Erikson: Identity’s Architect (Harvard University Press, 1999). He’s currently working on a biography of one of the most influential psychologists and public intellectuals of the 20th century,

Erich Fromm.

"Erich Fromm and the Public Intellectual in Recent American History: An Interview with Larry Friedman," conducted by Randall Stephens,

Historically Speaking, September 2010.

Randall Stephens: The popular psychologist and social critic Erich Fromm was once one of the most influential public intellectuals in the West. Yet many are unfamiliar with his life and work today. Could you say something about his context and significance?Larry Friedman: Yes, that’s true. But his influence is still felt in many quarters around the globe and, as you say, he was once a major public figure. . . .

Fromm is significant for a number of reasons. But, perhaps most importantly, he had a wide influence as a best-selling author. His first book,

Escape from Freedom (1941), linked Nazi and authoritarian regimes with the individual’s fear of freedom and autonomy. To escape from freedom was to find a greater sense of order in sadomasochism and its cycle of degrading others. Fromm’s

The Sane Society (1955) railed against consumerism and made the case for local face-to-face democracy. His most enduring and popular work,

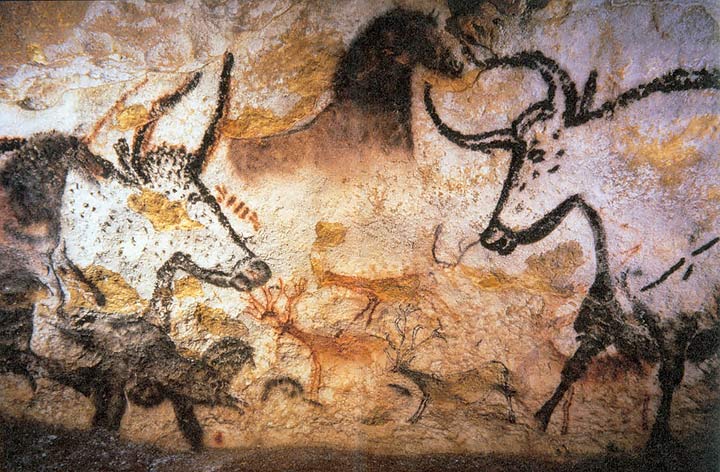

The Art of Loving (1956), called for the love of self as a central component in the capacity to befriend and love others. It sold a staggering 30 million copies globally and was available in airports, drug stores, you name it. In 1973 he published The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, which suggested that a conflict exists in all people between necrophilia and biophilia, a rage for death and annihilation on one hand and an affirmation and love of life on the other. To complete this book, Fromm took up the study of neuroscience, physical anthropology, linguistics, and other fields far outside of his training in psychoanalysis to explain why some favored death and destruction while others preferred life and love. We might speculate that if mainline psychoanalysis had branched into other fields as Fromm had done, psychoanalysis might have escaped the doldrums of recent decades. . . .

Stephens: How relevant are [Erich] Fromm's interests and causes to the average educated reader today?Friedman: For one, his writings on war and devastation are still remarkably discerning. Of course, in Escape from Freedom he was concerned with the perils of Nazism and Stalinism. But he also pointed to future developments, like McCarthyism and the Red Scare. And he is exceedingly relevant even to today's world. Take, for instance, his position on the Mideast, specifically Israel. He was very critical of Israeli belligerence. His views bear some resemblance to those of Noam Chomsky.

Stephens: Your historical work has had a heavy psychological component. What's your opinion of the psychohistory of the 1960s and 1970s? Friedman:

Friedman: I thought much psychohistory had become reductionist by the late 1960s. I felt that it was giving psychological exploration a bad name. It overemphasized the psychoanalytical element and did not employ cognitive psychology or neuroscience. It tended to be ahistorical. Now what is sometimes called the new cultural history is heavily psychological, but less reductionist than the old psychohistory of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Stephens: Your next book is about Richard Hofstadter and the mid-century New York scene. I wonder if you'd say something about that.Friedman: Hofstadter was one of the greatest historians of the modern era. You can say he's wrong on a number of points, but he's brilliantly wrong and always worth going back to. Current debates about the role of conservative religion in America or the influence of anti-intellectualism revolve around some of Hofstadter's basic ideas. His take on the American political tradition continues to influence high school curricula. He remains amazingly relevant. What interests me especially is mid-century New York City. His friends and associates who lived there, intellectual giants like Peter Gay, helped shape our basic understandings of history and culture. Hofstadter also interacted with Manhattan's theater community and art world. Hofstadter's New York in the 1950s and 1960s was a fascinating intellectual and cultural hub.

>>>